Guest post by Rodger Dean Duncan

An entrepreneur, it’s been said, isn’t someone who owns a business. It’s someone who makes things happen.

Arguably, successful entrepreneurship is less about venture capital and more about bringing good ideas to fruition. It’s less about college pedigrees and more about envisioning better solutions (just ask dropout Bill Gates).

Think about it. Hewlett-Packard started in a garage. Facebook was born in a dorm room. Amazon was hatched by people who saw possibilities with a retail system that had nothing to do with brick and mortar.

In short, successful entrepreneurs view life through a different lens.

To explore some provocative thinking on the subject, I talked with Randy Gage. He’s the author of Mad Genius: A Manifesto for Entrepreneurs.

Rodger Dean Duncan: You reject the notion that“genius” is just a function of IQ. In a nutshell, what are the key ingredients of “genius” thinking and behavior?

Randy Gage: It’s doubtful anyone would deny that Amy Winehouse, Ernest Hemmingway or Ginger Rogers were geniuses. But I don’t know that any of them possessed a genius IQ. Their brilliance—like many of us—came not from a cognitive intellectual measurement, but the way they expressed their unique gifts to the world.

Duncan: You note that even brilliant entrepreneurs sometimes create breakthrough products or concepts—only to devolve into mediocre practices of the market space they want to disrupt. Why is the mediocrity trap so seductive?

Gage: The mediocrity trap is so seductive because you slide into it without even realizing you have. So an entrepreneur creates a breakthrough product, gets his team together and asks everyone how they should take it to market. Someone says, “Well, this is how products are usually launched…” or “This is how our competitors launched theirs…” and suddenly you are back in the land of mediocrity.

Duncan: Really successful organizations seem to encourage their people to behave more like entrepreneurs than like lock-step employees. What are the keys to creating a culture that consistently produces “mad genius” results?

Gage: You have to be willing to let people fail without fear of losing their job or your confidence. In fact,you have to encourage them to be bold and know that they will sometimes fail.But it’s a mistake only if you don’t learn from it. And you have to work relentlessly to kill the politics that invariably spring up in large organizations. It’s vital to create a “safe space” for creative people to be brilliant.

Duncan: When asked if Apple did focus groups for the iPad, Steve Jobs famously replied that it wasn’t the customers’ job to know what they wanted. You say it’s the entrepreneur’s job. How does that philosophy fit into the Mad Genius paradigm?

Gage: Your clients or customers sometimes know the end result they wish to receive, but not how to achieve that. And often they don’t even know the result they want to get; only what they want to avoid.

Our role as entrepreneurs is to solve problems, add value and most importantly, see possibilities. When we are willing to do the intellectual and creative work of foreseeing possibilities for our customers and clients, we can sometimes envision a product they have no idea they want—until they actually see it.

Duncan: You suggest that “the smarter you are, the greater the likelihood you are intellectually lazy.” Why is that, and what can smart people do about it?

Gage: Unfortunately, my experience here comes from myself. Sometimes we are too clever for our own good. When we are smart in an area, we start to think we can take shortcuts. But there is always a process that has to be followed from a sound premise to a logical conclusion. We have to be smart enough to realize we’re not that smart!

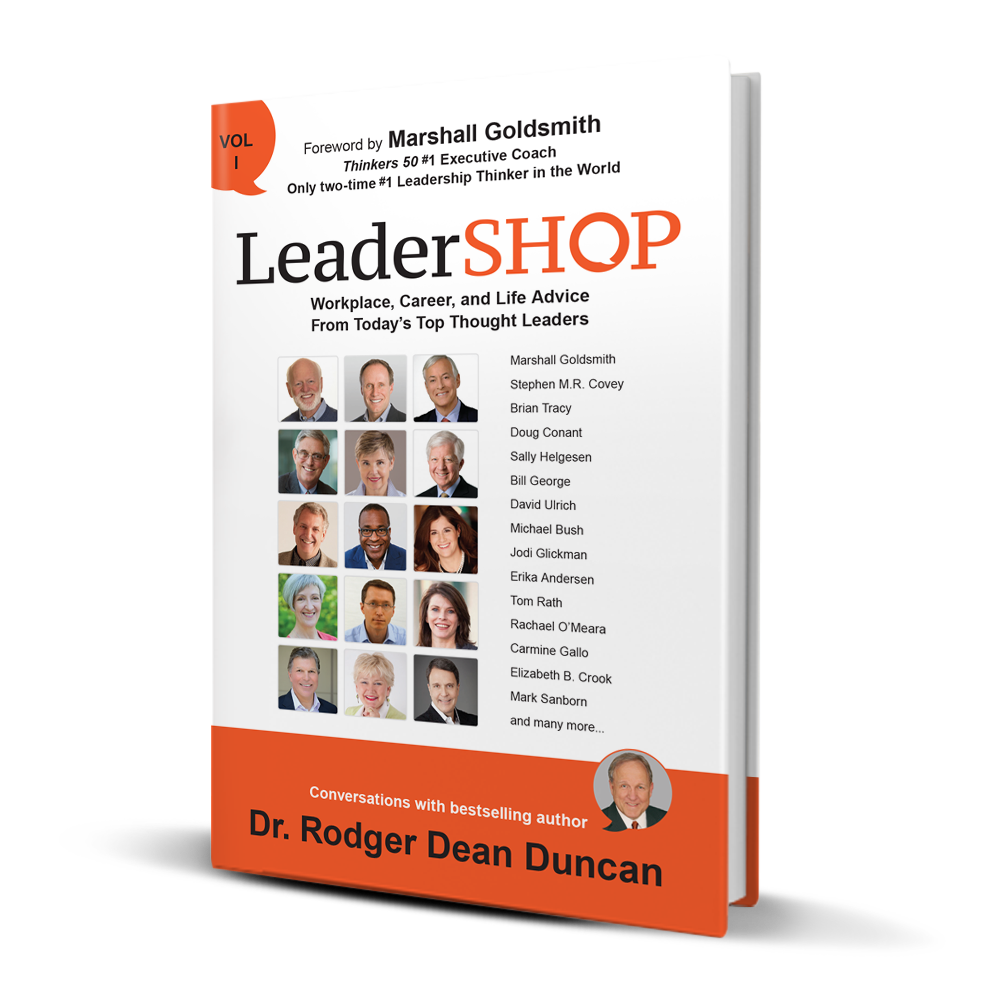

Rodger Dean Duncan is bestselling author of LeaderSHOP: Workplace, Career, and Life Advice From Today’s Top Thought Leaders. Early in his career he served as advisor to cabinet officers in two White House administrations and headed global communications at Campbell Soup Company. He has coached senior leaders in dozens of Fortune 500 companies.

This guest post originally appeared on Forbes