Today’s global economy is forcing a shift in the role human resources plays in organizations, moving from a transactional-administrative role to a strategic partner and facilitator of an organization’s most important asset – its people. However, projects in human resources and their functions may find it particularly difficult to obtain funding, and are typically one of the first things to be cut when budgets are tight. This unfortunate reality is principally due to human resource’s inability to align a credible business case followed by positioning it with key executives as having a quantifiable, direct impact on the bottom-line of the organization. Breitfelder and Dowling (2008) suggest human resources sits in the middle of some of the most compelling and competitive battlegrounds in business, where organizations deploy and fight over that most valuable of resources, their talent. Therefore, building a business case for talent management has become a strategic imperative for human resources professionals that will buttress an organizations ability to achieve its goals and objectives and in due course improve the performance of the bottom-line.

What is Talent Management?

The term talent management was conceived many years ago and initially referred to the programs used to manage and develop the top talent in an organization. Today, it has transformed into a key strategic and sustainable competitive advantage for organizations who are looking to recruit and retain talented employees throughout an organization. Where it was once for only the hand-picked few is now for many employees throughout an organization. Talent management today can be viewed from a holistic and strategic view and may be defined as a method to optimizing human capital through integrated organizational processes designed to attract, retain, develop, motivate and deploy employees, with the goal to create strong culture, engagement, capability, and capacity that meets current and future organizational objectives. Avedon and Scholes (2010) suggest talent are employees with strategic importance to the purpose and objectives of the organization. However, in today’s workplace it has expanded beyond the strategic few at the top to the strategic many deep and wide in the organization.

Building the Business Case

When building the business case, human resource leaders must structure it in a way that business leaders can understand the need. Building the business case for talent management begins by defining a strategy in the context of the business strategy. In other words, the strategy should help the organization to achieve its business goals through focusing on its talent. Business leaders understand the need to make money and talent management, when done well, makes money (Bersin, 2012). Therefore talent management needs to move away from just being a human resources project or program and forward towards being a true sustainable business strategy.

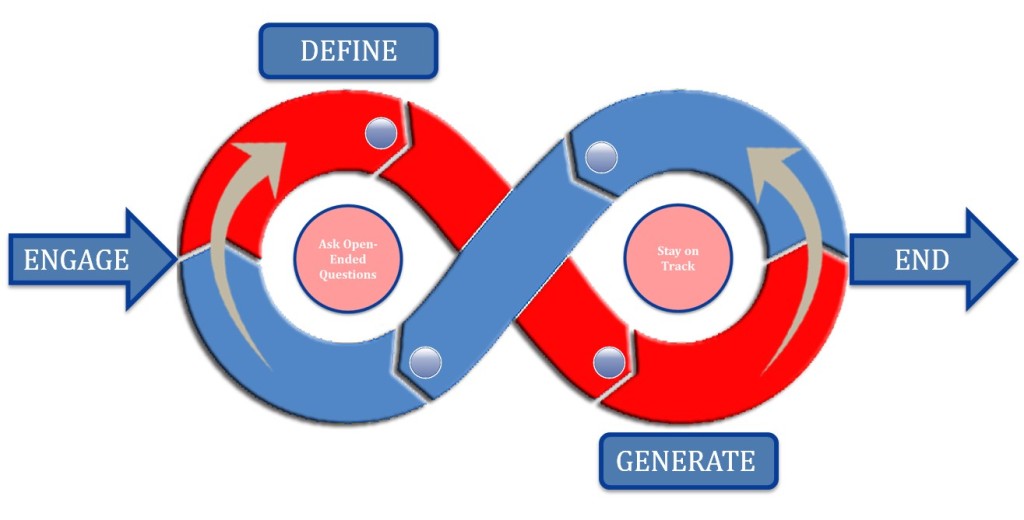

Strategy is about change and should not stand alone as a management process (Kaplan and Nadler, 2001). A talent management strategy needs to describe what the changes will be and how the changes will happen. Strategy maps can help by describing the changes an organization would like to bring about and, just as importantly, the systems and processes that ensure those changes happen. Kaplan and Nadler (2001) see strategy maps explaining what will be different and how organizations change in a cohesive, integrated and systematic way. In that same vein, human resource leaders will face a nearly impossible challenge to persuade executives to fund a business case for a talent management strategy if it fails to reflect a genuine understanding of the business. Consequently, strategy is also about a series of choices to do things differently than competitors so to provide a unique and attractive value proposition to attract, manage, develop, motivate and retain key people. (Kaplan and Nadler, 2001). Mapping a talent management strategy will be integral in demonstrating how an investment in talent management processes and programs can deliver value to the organizations customers and the bottom-line.

Organizational Benefits

Organizational benefits of a talent management strategy will vary depending on the industry and mission, vision, and goals of the organization. Bersin (2011) adds that talent management is not something to copy from a book and that the strategy will be unique to the organization as well as the benefits. However, a structured talent management strategy will systematically close the gap between the current human resources in an organization and the talent it will ultimately need in order to respond to business challenges in the future (Smith, Wellins, and Paese, 2011). Closing this gap will mean the organization will be able to remain competitive and retain key talent, attract new talent, and assemble plans for key roles and people in the organization in order to allow for proper development experiences. According to a study by The Hackett Group, Inc. (2010), they found that organizations with strong talent management strategies were like to see an increase in their bottom-line earnings by 18 percent. Additionally a Bersin study from 2010-2011 showed that organizations deployed strategic talent management saw twice the revenue of other organizations, 40% less employee turnover, along with 38% higher levels of engagement (Bersin, 2011). So, the evidence is clear, organizations that spend money and time on strategic talent management efforts will see their investment essentially pay for itself.

Conclusion

Organizations that deploy effective strategic talent management practices truly understand that talent is a key competitive advantage. Building the business case will be the hardest part for human resources professionals, however, they can help themselves by genuinely understanding the business and seek and give guidance to the executives who generally do not want to invest their time in these processes. Building the business case and coupling it with a strategy map will provide for a simple and powerful way for the human resources professional to demonstrate value and communicate visually how the strategy can be executed. Additionally, it will be critical for the human resources professional to decouple the strategy from being just a human resources initiative but instead a whole organization or business initiative. Doing this will allow for human resources to be viewed as a true strategic business partner. When organizations leverage strategic talent management practices they can project confidence to their market and remain nimble and flexible regardless of the market conditions.

References

Avedon, M. J., & Scholes, G. (2010). Building Competitive Advantage through Integrated Talent Management. In Silzer, R. F., & Dowell, B. E. (Eds.), Strategy-driven talent management: A leadership imperative (73-116). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Bersin, J. (2012, January 22). The Business Case for Talent Management: Steve Ballmer Agrees. Retrieved from http://www.bersin.com/blog/post/2012/01/The-Business-Case-for-Talent-Management--Steve-Ballmer-Agrees.aspx

Breitfelder, M.D., & Dowling, D.W. (2008, July-August). Why Did We Ever Go Into HR? Harvard Business Review, 86, 39-43.

Kaplan, R.S. & Nadler, D.P. (2001). Building Strategy Maps. In Kaplan, R.S. & Nadler, D.P. The Strategy- focused organization: How balanced scorecard companies thrive in the new business environment (pp. 69-105). Boston: Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

Smith, A.B., Wellins, R.S. & Paese, M. (2011). The CEO’s Guide To: Talent Management A Practical Approach. Pittsburgh, PA. Development Dimensions International. Retrieved from http://www.ddiworld.com/ddiworld/media/booklets/ceoguidetotalentmanagement_bk_ddi.pdf?ext=.pdf

Study Finds Experienced Talent Management Brings Higher Earnings & Other Benefits. (2010). HR Focus, 87(3), 8-9.

“Increased precision through adaptive testing makes this the best DiSC on the market. Don’t settle for imitations!”

“Increased precision through adaptive testing makes this the best DiSC on the market. Don’t settle for imitations!”